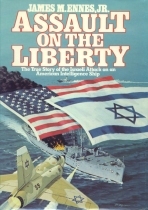

The True Story of Israel's attack

on an American Intelligence Ship

By James M. Ennes, Jr.

Chapter Six

AIR ATTACK

Copyright by James Ennes 1980, 1986, 1995, 2002, 2004, 2005

Imagine all the earthquakes in the world, and all the thunder and

lightnings together in a space of two miles, all going off at once.

--Description by unknown U.S. Army officer of night engagement when

Farragut ran Fort Jackson and St. Philip, April 24, 1862

Searing heat and terrible noise came suddenly from everywhere.

Instinctively I turned sideways, presenting the smallest target to the

heat. Heat came first, and it was heat--not cannon fire--that caused me to

turn away. It was too soon to be aware of rockets or cannon fire.

"We're shooting!" I thought. "Why are we shooting?" The air

filled with hot metal as a geometric pattern of orange flashes opened

holes in the heavy deck plating. An explosion tossed our gunners high

into the air-spinning, broken, like rag dolls.

My first impression--my primitive, protective search for

something safe and familiar that put me emotionally behind the gun--was

wrong. We were not firing at all. We were being pounded with a deadly

barrage of aircraft cannon and rocket fire.

A solid blanket of force threw me against a railing. My arm

held me up while the attacker passed overhead, followed by a loud

swoosh, then silence.

O'Connor spotted bright flashes under the wings of the

French built jet in time to dive down a ladder. He was struck in midair,

severely wounded by rocket fragments before he crashed into the deck

below.

I seemed to be the only one left standing as the jet

disappeared astern of us. Around me, scattered about carelessly, men

squirmed helplessly, like wounded animals--wide-eyed, terrified, not

understanding what had happened.

The second airplane made a smoky trail in the sky ahead. Unable

to move, we watched them make a sweeping 180-degree turn toward Liberty,

ready to resume the attack. My khaki uniform was bright red now from two

dozen rocket fragments buried in my flesh. My left leg, broken above the

knee, hung from my hip like a great beanbag.

The taste of blood was strong in my mouth as I tested my good

leg. Was I badly hurt? Could I help the men floundering here? Could I

help myself. Was it cowardice to leave here?

On one leg, I hopped down the steep ladder, lurched across the

open area and fell heavily on the pilothouse deck just as hell's own

jackhammers pounded our steel plating for the second time. With

incredible noise the aircraft rockets poked eight-inch holes in the

ship; like fire-breathing creatures, they groped blindly for the men

inside.

Already the pilothouse was littered with helpless and

frightened men. Blood flowed, puddled and coagulated everywhere. Men

stepped in blood, slipped and fell in it, tracked it about in great

crimson footprints. The chemical attack alarm sounded instead of the

general alarm. Little matter. Men knew we were under attack and went to

their proper places.

Captain McGonagle suddenly appeared in the starboard door of

the pilothouse and ordered: "Right full rudder. All engines ahead flank.

Send a message to CNO: 'Under attack by unidentified jet aircraft,

require immediate assistance.' "

Grateful for an order to execute, confident that only this man

could save them, the crew responded with speed and precision born of

terror. Never have orders been acknowledged and executed more quickly.

These were brave men. These were trained men. But these were also

confused and frightened men inexperienced in combat. An order told them

that something was being done, made them a part of the effort, gave them

something to take the place of the awful fear.

Reacting to habit as much as to duty, and grateful that duty

required his quick exit from this terrible place, Lloyd Painter looked

for his relief so that he could report to his assigned damage control

station below. Finding Lieutenant O'Connor half dead in a limp and

bloody heap at the bottom of a ladder, he demanded: "Are you ready to

relieve me?"

"No, I'm not ready to relieve you," O'Connor mimicked weakly

--aware, even now, of the irony. McGonagle interrupted to free Lloyd of

his bridge duty.

I lay next to the chart table, unable to control the blood flow

from my body and wondering how much I could lose before I would become

unconscious. Blood from my chest wound was collecting in a lump in my

side so large that I couldn't lower my arm. My trouser leg revealed a

steady flow of fresh blood from the fracture site. Numerous smaller

wounds oozed slowly. Next to me lay Seaman George Wilson of Chicago, who

had stood part of his lookout watch this morning without binoculars. In

spite of a nearly severed thumb, Wilson used his good arm and my web

belt to fashion a tourniquet for my leg, effectively slowing the worst

bleeding. Someone opened my shirt, ripping off my undershirt for use

somewhere as an emergency bandage. Meanwhile, I wrapped a handkerchief

tightly around Wilson's wrist to control the bleeding from his hand. In

this strange embrace we received the next airplane.

BLAM! Another barrage of rockets hit the ship. Although the

first airplane caused a permanent ringing in my ears and forever robbed

me of high-frequency hearing, the attacks seemed no less noisy. Men

dropped with each new assault. Lieutenant Toth, still carrying my unsent

sighting reports, received a rocket that turned his mortal remains into

smoking rubble. Seaman Salvador Payan remained alive with two jagged

chunks of metal buried deep within his skull. Ensign David Lucas

accepted a rocket fragment in his cerebellum. And still the attacks

continued.

In the pilothouse, Quartermaster Floyd Pollard stretched to

swing a heavy steel battle plate over the vulnerable glass porthole. A

rocket, and with it the porthole, exploded in front of him to transform

his face and upper torso into a bloody mess. Painter helped lead him to

relative safety near the quartermaster's log table before leaving the

bridge to report to his battle station.

On the port side, just below the bridge, fire erupted from two

ruptured fifty-five-gallon drums of gasoline. A great flaming river

inundated the area and poured down ladders to the main deck below.

Lieutenant Commander Armstrong-ever impulsive, ever gutsy, ever committed

to the job at hand-bounded toward the fire. "Hit, em! Slug the sons of

bitches!" he must have been saying as he fought to reach the

quick-release handle that would drop the flaming and still half-full

containers into the sea. A lone rocket suddenly dissolved the bones of

both of his legs.

Meanwhile, heretofore mysterious Contact X came to life with

the first exploding rocket. Quickly poking a periscope above the surface

of the water, American submariners watched wave after wave of jet

airplanes attacking Liberty. Strict orders prevented any action that

might reveal their presence. They could not help us, and they could not

break radio silence to send for help. Frustrated and angry, the

commanding officer activated a periscope camera that recorded Liberty's

trauma on movie film. He could do no more. 1

Dr. Kiepfer, en route to his battle station in the ship's sick

bay, stopped to treat a sailor he found bleeding badly from shrapnel

wounds in a passageway. A nearby door had not yet been closed, and

through the door Kiepfer could see two more wounded men on an exposed

weather deck. Cannon and rocket fire exploded everywhere as the men

tried weakly to crawl to relative safety.

"Go get those men," Kiepfer yelled to a small group of sailors

as he worked to control his patient's bleeding.

"No, sir," "Not me," "I'm not crazy," the frightened men

whimpered as they moved away from the doctor.

No matter. Kiepfer would do the job himself. As soon as he

could leave his patient, Kiepfer moved across the open deck. Ignoring

bullets and rocket fragments, the huge doctor kneeled beside the wounded

men, wrapped one long arm around each man's waist, and carried both men

to safety in one incredible and perilous trip.

Lieutenant George Golden, Liberty's engineer officer, was in

the wardroom with Ensign Lucas when the attack began. A meeting had been

planned for Golden, Scott, Lucas and McGonagle to discuss the drill. The

captain was still on the bridge, so the meeting would be delayed. Scott

was slow to arrive, as today was his twenty-fourth birthday and he was

at the ship's store picking out a Polaroid camera to help celebrate the

occasion.

Golden was pouring coffee when they heard the first explosion.

"Jesus, they dropped the motor whaleboat!" he cried as he abandoned his

cup and started toward the boat. Then he heard other explosions and knew

even before the alarm sounded that Liberty was under attack.

Reversing his path, he started toward his battle station in the

engine room just in time to see Ensign Scott open the door to his

stateroom and slide his new camera across the floor before racing to his

battle station in Damage Control Central.

A rocket penetrated the engine room to tear Golden from the

engine-room ladder. He plunged through darkness, finally crashing onto a

steel deck, miraculously unhurt. He could see rockets exploding

everywhere, passing just over the heads of his men and threatening vital

equipment. "Get down!" he yelled. "Everybody stay low; on your knees!"

Golden knew that the bridge would want maximum power. Already

Main Engine Control had an all-engines-ahead-flank bell from the bridge

that they could not answer. Flank speed was seventeen knots, but Golden

had taken one boiler off the line just ten minutes earlier so that it

could cool for repairs. Without that boiler the best speed he could

provide was about twelve knots. He immediately put the cooling boiler

back on the line and started to bring it up to pressure.

Even with both boilers on the line, the engines were limited by

a governor to eighteen knots. For years Golden had carried the governor

key in his pocket so that he could find it quickly in just such an

emergency as this. He switched the governor off, permitting the ship to

reach twenty-one knots.

As machine-gun fire and aircraft rockets battered the ship, the

main engine room began to take on the appearance of a fireworks display.

Most lighting was knocked out in the first few minutes, leaving

flashlights and battle lanterns as the only illumination in the room

except for a skylight six decks above. In this relative darkness, men

worked on hands and knees, operating valves, checking gauges, starting

and stopping equipment, bypassing broken pipes; and all the while above

them danced white, yellow, red and green firefly like particles. Some

were small. Some were huge and burst into pieces to shower down upon

them. All entered the room with a tremendous roar as they burst through

the ship's outer skin.

Golden glanced at the scene above him. It reminded him of

meteor showers, except for the noise, or of electric arc welding. Most

of his men were here now, having safely descended the ladders through

the fireworks to reach their battle stations. Boiler Tender Gene Owens

was here and in charge of auxiliary equipment on the deck below Golden.

Machinist Mate Chief Richard J. Brooks was here. Brooks was petty

officer in charge of the engine room, and he was everywhere.

Golden realized suddenly that far above them, directly in

the range of rocket and machine-gun fire, was a hot-water storage tank.

Five thousand gallons of near- boiling water lay in that tank, ready to

pour down upon them if it was ruptured, and it would surely be ruptured.

The drain valve was at the base of the tank, so it would be necessary to

send a man up more than three decks to open the valve.

Golden quickly explained to a young sailor what had to be done

and sent him on his way, but the frightened man collapsed on the deck

grating and refused to move.

Chief Brooks overheard the exchange. "C'mon, you heard the

lieutenant. Move!" he cried, jerking the panic-stricken teenager to his

feet.

Terror was written on the young man's face. Tears started to

flow as his face contorted in a grimace of fear.

With a snarl of contempt, Brooks gave him a shove that sent him

sprawling. Then Brooks mounted the ladder leading to the vital drain

valve. Two decks above, perhaps fifteen feet up the ladder, a tremendous

explosion occurred next to Brooks. In a shower of sparks and fire, he

was torn from his place on the ladder and thrown into space to land

heavily upon the steel grating below. Brooks was back on his feet before

anyone could reach him. Back up the same ladder he headed until he found

the valve, opened it and drained the water only moments before the

inevitable rocket hit the storage tank to find it newly empty.

In a few minutes, most of the battle lanterns had been struck

by rocket fragments or disabled by the impact of nearby explosions. The

room was nearly dark. By working on hands and knees, men could remain

below the waterline and thus below most of the rocket and gunfire,

although they were still vulnerable to an occasional wildly aimed rocket

and to the constant shower of hot metal particles from above.

When fresh-air fans sucked choking smoke from the main deck into the

engine rooms, Golden ordered the men to cover their faces with rags and

to try to find air near the deck. When the smoke became intolerable, he

sent a message to the bridge that he would have to evacuate; but just

before Golden was to give the evacuation order, McGonagle ordered a

course change that carried the smoke away from the fans. Fresh air

returned at last to the engine room.

The first airplane had emptied the gun mounts and removed

exposed personnel. The second airplane, through extraordinary luck or

fantastic marksmanship, disabled nearly every radio antenna on the ship,

temporarily preventing our call for help.

Soon the high-performance Mirage fighter bombers that initiated

the attack were joined by smaller swept-wing Dassault Mystyre jets,

carrying dreaded napalm--jellied gasoline. The Mystyres, slower and more

maneuverable than the Mirages, directed rockets and napalm against the

bridge and the few remaining topside targets. In a technique probably

designed for desert warfare but fiendish against a ship at sea, the

Mystyre pilots launched rockets from a distance, then dropped huge

silvery metallic napalm canisters as they passed overhead. The jellied

slop burst into furious flame on impact, coating everything, then surged

through the fresh rocket holes to burn frantically among the men

inside.'

I watched Captain McGonagle standing alone on the starboard

wing of the bridge as the whole world suddenly caught fire. The deck

below him, stanchions around him, even the overhead above him burned.

The entire superstructure of the ship burst into a wall of flame from

the main deck to the open bridge four levels above. All burned with the

peculiar fury of warfare while Old Shep, seemingly impervious to

man-made flame and looking strangely like Satan himself, stepped calmly

through the fire to order: "Fire, fire, starboard side, oh-three level.

Sound the fire alarm."

Fire fighters came on stage as though waiting in the wings for a

prearranged signal. Streaming through a rear pilothouse door, they

carried axes, crowbars, CO, bottles and hundreds of feet of fire hose.

The sound of CO, bottles and fire-hose sprinklers added to the din as

the smell of steam overtook the smell of nitrates, smoke and blood. Men

screamed, cried, yelled orders and scrambled to duty as the ship

struggled to stay alive.

On the forecastle, Gunner's Mate Alexander N. Thompson fought

his way relentlessly toward the forward gun mount. Only moments before,

Thompson had remarked to me on the bridge: "No sweat, sir. If anything

happens I just want to be in a gun mount." Now he was repeatedly driven

away by exploding rockets. Weakened, with duty waiting in that small gun

tub, he tried again.

His radar disabled, Radarman Charles J. Cocnavitch left his

post to man a nearby gun mount. "Stay back!" Captain McGonagle ordered,

knowing that the gun would be ineffective and that Cocnavitch would die

in a futile attempt to fire. Meanwhile, Lieutenant O'Connor, still lying

near the ladder where he had fallen, was robbed of any latent prejudices

by huge black Signalman Russell David, who braved fire, blast and

bullets to move the limp and barely conscious officer from the bridge to

safety in the now-empty combat information center.

The pilothouse became a hopeless sea of wounded men, swollen

fire hoses and discarded equipment. Men tripped over equipment, stepped

on wounded. In front of the helmsman a football-size glob of napalm

burned angrily, adding to the smoke and confusion. Smaller napalm globs

burned in other parts of the room, refusing to be extinguished.

Again I thought of duty. My duty was on this bridge, amid the

flame and the shrapnel, driving this ship and fighting to protect her.

Already I was weak from loss of blood and from the shock of my wounds. A

sailor tripped over me, stepped on Seaman Wilson, and fell on other

wounded as he dragged a CO, bottle across the room. I decided that duty

did not require that we all lie here and bleed. It may even require that

we get out of the way, if we can, so that others may fight.

Relinquishing Wilson's tourniquet to Wilson, he released mine. Acutely

conscious of my retreat from the heart of battle, I raised an arm toward

some sailors huddled nearby. Seaman Kenneth Ecker pulled me to my feet

and I resumed my one-legged hopping.

I need a place to plug my wounds, I told myself, a place to

find the holes and stop the flow of blood.

I hopped out of the room. Ecker stayed with me, adding to the

guilt I felt for leaving the bridge. Bad enough that I should leave, but

to take the bridge watch with me! "Go back!" I insisted. Ecker stayed.

The ladder leading from the pilothouse was thick with fire hoses.

Somewhere beneath the hoses were solid ladder rungs, but my foot could

find only slippery fire hoses. With one hand on each railing and with my

beanbag catching awkwardly on every obstruction, I hopped clumsily down

the ladder. Once I stood aside to let a man pass in the other direction

with a C02 bottle. He stopped to stare at me with a startled look, his

mouth open. "Hurry!" I said. I reached the level below to find Ecker

still with me. "Go back!" I protested again.

Lightheaded from loss of blood, I searched for a place to

examine my injuries and to treat my wounds. The search became urgent as

I became increasingly dizzy. More airplanes pounded our ship as I

discovered that the captain's cabin offered no refuge. Through his door

I could see a smoke-filled room with gaping holes opening to the flame

outside, and frantic napalm globs eating his carpet.

Around a corner I found the doctor's stateroom. The room was

dark, the air free of smoke. His folding bunk was open from a noontime

nap, his porthole closed with a steel battle plate. Strangely concerned

that I was soiling his sheets with blood, I pulled myself onto his clean

bed. My useless left leg hung over the side in a sitting position.

Ecker, still nearby, wanting to help but afraid to touch the leg,

finally laid it gingerly alongside the other. I thought of the tissue

being abused and wondered how close the sharp bone ends were to the

artery.

What happens if I cut the artery ? I wondered. Maybe I have

already. A thousand questions begged for answers: Did we get our message

off? Will they never stop shooting? When will our jets arrive? And who

is shooting at us, anyway?

We still had no idea who was attacking. Although the Arab

countries largely blamed the United States for their problems and

falsely charged that American carrier-based aircraft had assisted

Israel, we knew that the Arab air forces were crippled and probably

unable to launch an attack like this one. And to increase the confusion,

a ship's officer thought he saw a MIG- 1 5 over Liberty and quickly

spread a false report among the crew that we were being attacked by the

Soviet Union. Probably no one suspected Israeli forces.

I took a few still-painful breaths to clear my head before tending

my wounds. Ecker hovered nearby, forcing my conscience to remind me that

I should be on the bridge; worse, that an able-bodied man was away from

his battle station to help me.

With each movement I could feel the tear of sharp bone end

against muscle. I was only abstractly aware of pain; instead, I was

conscious of fear, of duty abandoned on the bridge, and of an urgent

knowledge that, no matter what else might happen, I would almost surely

die if I didn't soon stem the flow of blood, particularly from the leg

wound.

I reached for Dr. Kiepfer's sheets to make a more effective

tourniquet when suddenly four deadly rockets opened eight-inch holes to

tear through the steel bulkhead into the room. Blast, fire, metal passed

over my head and continued through an opposite wall. Ecker, standing in

the open doorway, was startled but unhurt; several thumb-size holes at

forehead level verified the utility of his battle helmet as he raced

away to answer a call for firefighters.

My bare chest glowed with a hundred tiny fires as burning

rocket fragments and napalm-coated particles fell on me like angry

wasps. Desperately I brushed them away. As the tiny flames died, the hot

metal continued to sear my chest. The room filled with smoke as the

carpeting near me and the bedding around me burned with more small

fires.

Through the fresh rocket holes I could see a tremendous fire

raging on deck outside and I could hear the crackle of flames. The motor

whaleboat burned furiously from a direct napalm hit while other fires

engulfed the weather decks and bulkheads nearby. Directly above me on

the next deck, I realized, were a gun mount and a radio antenna. Both

were obvious targets. I would have to leave this place.

My leg pinned me to the bunk. It blocked my movement, weighed

me down, prevented my escape from the additional rockets that were sure

to come. I considered and quickly dismissed sliding under the mattress

for protection. With the last of my strength I used my good leg to evict

the useless broken limb from the bunk. Would this open the artery? I had

to take the chance as the sharp bone ends again sliced through muscle.

With great effort I forced myself up,rolled out onto my good right leg,

and hopped away once more toward what I hoped would be safer ground,

closing the door behind me.

The door, closed by habit, shielded me from a new blast and

probably saved my life as a rocket penetrated the room from above,

blasting through the heavy deck plating and air ducts in the overhead

to explode with such force that the heavy metal door was torn from its

frame. I fell to the deck outside.

On the bridge, the helmsman fell wounded as another assault

sent rocket fragments through steel and flesh. Almost before he fell,

his post was taken by Quartermaster Francis Brown. The Quartermaster of

the watch is the senior enlisted man on duty and is responsible for the

performance of the men. Friendly, hard-working, cooperative, Brown was a

popular member of the bridge team. I was always pleased when Brown was

on duty with me. He never needed to be told what to do. When Brown was

on watch, if a helmsman was slow to respond to an order or if a man had

trouble with bridge equipment, he spotted and corrected the problem

without being told. Now, typically, he saw his duty at the unattended

helm.

The gyro compass no longer worked. It was disabled by three

rockets that rode in tandem through the gyro room, passing harmlessly

between a group of sailors, smashing the equipment and leaving a

three-foot hole in a steel door on the way out. The magnetic

compass, meanwhile, spun uselessly, like a child's toy.

Gunner Thompson finally reached Mount 51 to find the gun

partially blocked by the body of Fireman David Skolak. Skolak had been

assigned to Repair Two, but after Seaman Payan was wounded, leaving the

gun unmanned, Skolak left his repair party to take Payan's place. He was

quickly dismembered by a direct rocket hit. Very weak now, Thompson

forced himself toward Mount 52, some forty feet away on the ship's port

side. With luck he would be able to fire at the next attacking jet.

Long before our arrival in the area, most secret documents had

been placed in large weighted bags, ready to be thrown overboard if

necessary to keep them from an enemy. This was a precautionary measure,

frequently taken by ships operating in dangerous areas. Now, defenseless

and under attack, everything classified but not actually in use was to

be destroyed. The bags proved useless, as they were too large and heavy

to carry, and the water wasn't deep enough for safe disposal, anyway.

The ship's incinerator couldn't be used, as it was on the 03 level

within easy range of the airplanes. As a last resort, Lieutenant

Pierce, the ship's communication officer, ordered his men to destroy

everything as best they could by hand. Acrid smoke soon filled the room

as he and Joe Lentini dropped code lists, a handful at a time, into a

flaming wastepaper basket; nearby, Richard Keene and Duane Marggraf

attacked delicate crypto equipment with wire cutters and a sledge

hammer.

In the TRSSComm room, equipment finally in full operation,

operators had just begun to talk with their counterparts at Cheltenham,

Maryland, when rockets suddenly undid all their work to disable the

system forever. A shower of sparks cascaded from high-voltage wires

overhead, bathing the men and equipment below in melted copper and

filling the room with the smell of ozone. Operators at Cheltenham did

not learn until much later why Liberty stopped talking in mid-sentence.

A code-room Teletype operator on Liberty's third deck pounded

desperately on a keyboard, trying to send the ship's cry for help.

Getting no answer, he tried other equipment until someone finally

noticed that a vital coding device had been removed for emergency

destruction, disabling the machine. The operator tried again. Still

nothing. Vividly aware of the nearness of death, the man was speechless

with terror. His voice came in senseless gasps and his body shook; he

wet his pants in fear, but he remained at his post and continued to

hammer his message into the keyboard. Still no answer. In the rush to

reinsert the coding device, the wrong device had been used. "Forget the

code," cried Lieutenant Commander Lewis when he saw the problem. "Go out

in plain language!"

Still the message failed to leave the ship. No one knew that

all our antennas had been shot down.

From where I fell outside the doctor's stateroom I could hear

the flames, the loud hiss of CO, bottles, the rush of water from fire

hoses and the sharp crunch as water became steam against hot steel.

Smoke was everywhere.

A young sailor plummeted hysterically down a ladder, crying,

"Mr. O'Connor is dead! He's in combat and he's dead!" then disappeared

on his grim mission, informing everyone of the death of my roommate and

long-time friend. I thought of Jim's wife, Sandy, pregnant; his infant

son; their pet schnauzer. Who will tell Sandy? My wife, Terry, will

console her, help her. Maybe they'll console each other.

A sailor arrived with a pipe-frame-and-chicken-wire stretcher.

Judging my rank from the khaki uniform, Seaman Frank Mclnturff assured

me as he laid the stretcher at my side, "Don't worry, Chief, you'll be

all right." Then, startled when he noticed my lieutenant's bars, he

apologized grandly for the oversight. We both laughed as I assured him,

"That's okay. You can call me Chief."

I saw no point in moving from where I was. Surely there was no

time to treat wounded. If there was time, certainly there were enough men

near death to keep the medical staff more than busy. Mclnturff insisted

that the wardroom was in operation as an emergency battle dressing

station and that I should go there. He and his partner rolled me onto

the stretcher, my leg twisting grotesquely in the process. Then he tied

me in place with heavy web belting and hoisted the stretcher. The first

obstacle was not far away. The ladder leading down to the 01 deck

inclined at a steep angle. I will fall through the straps and down the

ladder, I thought. With my stretcher in a near vertical position, we

started down. My arms ached as I held the pipe frame to keep from

slipping; chicken wire tore my fingers; as I slid deeper toward the foot

of the stretcher I could feel the broken bone ends grinding together.

Suddenly all such concern was forgotten as another rocket assault

battered the ship. The now-familiar, ear-shattering, mind-destroying

sound of rockets bursting through steel raced the length of the ship.

I braced for the plunge down the ladder as holes opened in the

steel plating around us. Then, except for the flames, the machinery and

the fi relighting equipment, silence.

Following each rocket assault, the silence seemed unearthly; slowly we

would become aware of the other sounds, but the immediate sensation was

relief and a strange silence. In silence we found ourselves still alive,

still standing on our ladder and still breathing deeply. The next ladder

was no less steep, but passed easily without the rocket accompaniment.

We arrived next at the door of the wardroom, our destination,

where we were greg,-ted by more rockets, entering the room through an

opposite wall. White smoke hung in the air. A fire burned under the

empty dinner table.

"Where should we go?" Mclnturff asked. Nothing could be seen of

the battle dressing station that was supposed to operate here. Clearly,

the wardroom could not be used.

"Just put me down here," I told him. My stretcher was eased to

the ground at the open door as the two men returned to the bridge to

retrieve more wounded. "Move me away from the door!" I cried as more

rocket fragments hurtled through the open door and over my stretcher to

spend themselves on the nearby bulkhead. I was quickly moved; the door

was closed. The narrow passageway soon filled with wounded, frightened

men. A battle dressing station, I learned, had been set up in the chief

petty officers' lounge around the corner and was already filled with

wounded. Dr. Kiepfer was operating the main battle dressing station in

the enlisted mess hall one deck below while this auxiliary station was

being operated by a lone senior corpsman, Thomas Lee VanCleave.

If we can hold out for a few more minutes, I thought, Admiral

Martin's jet fighters will be overhead. This hope quickly passed as a

sailor kneeled at my side to inform me that all our antennas had been

shot away. "They put a rocket at the base of every transmitting antenna

on the ship," he said, "but there is one that I think I can repair. Do

you think I could go out there and try to fix it so we could get our

message off. " I assured him that he would be doing us all a great

service, but asked him to be careful.

Soon the radio room pieced together enough serviceable

equipment to send a message that would alert the Navy to our

predicament. An emergency connection patched the one operable

transmitter to the hastily repaired antenna. But as Radiomen James

Halman and Joseph Ward tried to establish voice contact with Sixth Fleet

forces, they found the frequencies blocked by a buzz-sawlike sound that

stopped only for the few seconds before each new barrage of rockets

struck the ship. Apparently, the attacking jets were jamming our radios,

but could not operate the jamming equipment while rockets were airborne.

If we were to ask for help, we had to do it during the brief periods

that the buzzing sound stopped. Using Liberty's voice radio call sign,

Halman cried, "Any station, this is Rockstar. We are under attack by

unidentified jet aircraft and require immediate assistance!"'

Operators in USS Saratoga, an aircraft carrier operating with

Vice Admiral Martin's forces near Crete, heard Liberty's call and

responded, but could not understand the message because of the jamming.

"Rockstar, this is Schematic," said the Saratoga operator. "Say

again. You are garbled."

After several transmissions Saratoga acknowledged receipt of

the message. The Navy uses a system of authentication codes to verify

the identity of stations and to protect against sham messages.

"Authenticate Whiskey Sierra," demanded Saratoga.

"Authentication is Oscar Quebec," Halman answered promptly, after

consulting a list at his elbow.

"Roger, Rockstar," said Saratoga at 1209*Z. "Authentication is

correct. I roger your message. I am standing by for further traffic."

Saratoga relayed Liberty's call for help to Admiral McCain in

London for action and, inexplicably, only for information to Vice

Admiral Martin and to Rear Admiral Geis (who commanded the Sixth Fleet

carrier force).

Several minutes later, having heard nothing from

COMSIXTHFLT, the Liberty operator renewed his call for help.

"Schematic, this is Rockstar. We are still under attack by

unidentified jet aircraft and require immediate assistance."

"Roger, Rockstar," said Saratoga. "We are forwarding your

message." Then Saratoga added, quite unnecessarily and almost as an

afterthought, "Authenticate Oscar Delta."

The authentication list now lay in ashes a few feet away.

Someone had destroyed it along with the unneeded classified material.

Frustrated and angry, the operator held the button open on his

microphone as he begged, "Listen to the goddamned rockets, you son of a

bitch!"

"Roger, Rockstar, we'll accept that," came the reply.'

Operators in the Sixth Fleet flagship Little Rock and in the

carrier America, meanwhile, had long since received Liberty's message.

America's Captain Donald Engen' was talking with NBC newsman Robert

Goralski when the message was brought to the bridge. "This is

confidential, Mr. Goralski!" Engen snapped. And Goralski respected the

warning.

Aircraft-carrier sailors know that certain airplanes are always

spotted near the catapults where they are kept fueled, armed and ready

to fly. They are maintained by special crews, they are flown by

carefully selected pilots, and they are kept under special guard at all

times. These are the "ready" aircraft. To visitors, they are almost

indistinguishable from other aircraft, but they are very special

aircraft indeed, and their use is an ominous sign of trouble. They carry

nuclear weapons.

No one in government has acknowledged that ready aircraft were

sent toward Liberty, and no messages or logs have been unearthed to

prove that nuclear-armed aircraft were launched; moreover, there is no

indication that release of nuclear weapons was authorized under any

circumstances,on that ready aircraft, which normally carry nuclear

weapons, were launched toward Liberty, and that the Pentagon reacted to

the launch with anger bordering on hysteria.Widely separated sources

have described the launch and subsequent recall of those aircraft in

detail, and the circumstances are compelling.

According to a chief petty officer aboard USS America, the

pilots were given their orders over a private intercom system as they

sat in their cockpits. A United States ship was under attack, they were

told, and they were given the ship's position. Their mission was to

protect the ship. Under no circumstances were they to approach the

beach.

Two nuclear-armed F-4 Phantom jets left America's catapults and

headed almost straight up, afterburners roaring. Then two more became

airborne to rendezvous with the first two, and together the four

powerful jets turned toward Liberty, making a noise like thunder. All

this activity blended so completely into the shipboard routine that few

of the newsmen suspected that anything was awry; those who asked were

told that this was a routine training flight.

"Help is on the way!"'

This short message was received by a Liberty radioman and

quickly passed to nearly every man aboard. Messengers ran through the

ship, calling, "They're coming! Help is coming!" Litter carriers and

telephone talkers passed the word along. I remembered Philip's warning

of the night before: "We probably wouldn't even last long enough for our

jets to make the trip."

Meanwhile, Navy radio operators at the Naval Communications

Station in Morocco worked to establish communications for the emergency.

Lieutenant James Rogers and the station commander, Captain Lowel Darby,

came immediately to the radio room, where Petty Officer Julian "Tony"

Hart quickly set up several circuits, including voice circuits with the

aircraft carriers and COMSIXTHFLT, and established a Teletype circuit

with CINCUSNAVEUR in London. When the men tuned to the high-command

voice network, they could hear USS Liberty, her operators still pleading

for help, and in the background the exploding rockets.

A Flash precedence Teletype message from COMSIXTHFLT coursed

quickly through the Morocco communication relay station, destined for

the Pentagon, State Department and the White House:

USS LIBERTY REPORTS UNDER ATTACK BY UNIDENTIFIED JET AIRCRAFT. HAVE

LAUNCHED STRIKE AIRCRAFT TO DEFEND SHIP. It seemed only seconds later

that a new voice radio circuit was patched into the room that was now

becoming a nerve center for Liberty communications. This was a

high-command Pentagon circuit manned by a Navy warrant officer, but once

contact was established the voice on the circuit changed. Every man in

the room recognized the new voice as that of the Secretary of Defense,

Robert S. McNamara, and he spoke with authority: "Tell Sixth Fleet to

get those aircraft back immediately," he barked, "and give me a status

report."

A few minutes later the Chief of Naval operations himself came

on the air. The circuit was patched through to the Sixth Fleet flagship,

and Admiral David L. McDonald bellowed: "You get those fucking airplanes

back on deck, and you get them back now!"

"Jesus, he talks just like a sailor," said one of the sailors

listening on a monitor speaker at Morocco.

Soon four frustrated F-4 Phantom fighter pilots returned from

what might have been a history-making mission. They might have saved the

ship, or they might have initiated the ultimate holocaust; their return,

like their departure, blended smoothly into the ship's routine and

raised no questions from the reporters who watched.

Another Flash message moved through the Morocco Teletype relay

station: HAVE RECOVERED STRIKE AIRCRAFT. LIBERTY STATUS UNKNOWN. At

about the same time, Hart relayed the same message to the Pentagon by

voice radio. Liberty was silent now. No one at Morocco knew whether the

ship was afloat or not, but they knew that if she still needed help she

would have a long wait.'

Mclnturff returned to the bridge to find Lieutenant Commander

Philip Armstrong, wounded but coherent and strong, sprawled on the floor

of the chart house. His trousers had been removed to reveal grave damage

to both legs just below the level of his boxer shorts. Two broken legs

kept him off his feet, but he remained in control.

"No more stretchers, Commander," Mclnturff advised, still

winded from his journey with me. "We'll have to take you down in this

blanket."

"No, get a stretcher!" Phillip insisted.

"No more stretchers," McInturff repeated as he laid the blanket

next to Philip, ready to roll him onto it.

"I'm not going anywhere in any goddamned blanket. Go get a

stretcher!"

"But sir, I . . ."

"Go! I know there are enough stretchers on this ship!"

"Yessir."

Certain that every stretcher had a man in it, usually a man too

badly injured to be moved, Mclnturff raced through the ship, frantically

searching for the required stretcher. He opened a door to the main deck,

remembering that he had once seen some stretchers stowed near a

life-raft rack. A cluster of rockets crashed to deck around him with a

deafening roar, showering the area with sparks. Shaken but not slowed,

Mclnturff knew only that he must find that stretcher and get it back to

the XO in the chart house. Finally, precious platform in hand, he

struggled back toward the sick and impatient executive officer. Up

ladders, around corners, tripping over discarded CO, bottles and the

near-solid mass of fire hoses covering the last ladder to the bridge, he

arrived again in the pilothouse to find Philip Armstrong waiting not too

patiently on the deck of the chart house. Although the battle still

raged outside, one-sided as it was, although the ship was still being

hammered every few seconds with aircraft rockets, Philip was not

involved and he was furious about it. He wanted desperately to be on the

bridge. He wanted to fight. If he could do nothing more, he would throw

rocks and shake his fist at the pilots as they hurtled past. But Philip

was rooted to two beanbags and could only lie there and rage. Someone

gave him a cigarette and he turned it into a red cinder almost in one

long drag. He asked for another.

He didn't complain as he was lifted, rudely, painfully, onto

the chicken-wire bed. He muttered something as the two sailors lifted

the stretcher and started away with him, but Mclnturff didn't understand

as all voices were drowned out by explodingrockets. Mclnturff dreaded

another trip down that treacherous ladder. He was afraid he would slip

on the fire hoses, dropping the XO and blocking the ladder. He was

exhausted. His heart pounded loudly in his chest, complaining of the

exertion until he thought it must rebel; but he had no time to think,

certainly not to rest. With Philip and his stretcher nearly on end,

Philip's fingers clawing the pipe frame to keep from abusing the

fractures, they made the left turn at the bottom of the steep ladder,

passed through the narrow door, and found themselves in a passageway

next to the captain's open cabin door.

"Put me down!" Philip ordered.

"But-"

"Put me down!"

"Sir, I-"

"Get me a life jacket!" Philip demanded loudly.

"But, sir, they're still shooting and-" "Goddamn it, get me a

life jacket!" Philip insisted. "I'm not moving from here until I have a

life jacket."

An unusually heavy barrage hit the ship. Mclnturff pushed the

XO's stretcher to relative safety against a bulkhead, and ducked into

the burning, smoke-filled captain's cabin. Quickly driven out by the

arrival of still more rockets, he heard Philip demand, more firmly:

"Damn it! I told you to get a life jacket!"

"Jeezus! There's shit comin' in everywhere, Commander!" he

pleaded as an explosion tore open a nearby door, but Philip still

insisted upon having a life jacket.

Disbelieving, Mclnturff obediently left Philip in the care of

his partner while he made another desperate trip through the ship,

searching wildly for the required life jacket. Finally, he located a

discarded jacket in the CPO lounge emergency battle dressing station and

forced himself back to where he had left the XO.

Gone! He was gone. During the insane search for a life jacket,

someone had taken the XO below. Certain that his heart would burst,

Mclnturff struggled back up the ladder, back to the carnage in the

pilothouse, to retrieve more wounded.

Most of the wounded had been removed from the bridge. It was

possible once again to walk across the pilothouse. Quartermaster Brown

stood at the helm. Captain McGonagle, suffer ing from shrapnel in his

right leg and weakened by loss of blood, remained in firm control of his

ship as he directed damage control and firelighting efforts. Ensign

David Lucas, the ship's deck division officer, had been "captured" by

the captain to serve as his assistant on the bridge. Now Lucas wondered

if he would ever see the baby girl born to his wife a few hours after

Liberty sailed from Norfolk. He quickly pushed such thoughts from his

mind; three motor torpedo boats were sighted approaching the ship at

high speed in an attack formation.

McGonagle dispatched Seaman Apprentice Dale Larkins to take the

torpedo boats under fire from the forecastle. Larkins was an apprentice

not because he was new to the sea, but because, for reasons of his own,

he had refused to take the examination for advancement. He was a large

man and a tough fighter. He had already been driven first from Mount 54,

then from Mount 53. Now he charged down the ladder and across the open

deck to take the boats under fire from Mount 51.

Captain McGonagle, looking through the smoke of the motor

whaleboat fire, saw a flashing light on the center boat. He called for

the gunners to hold their fire while he attempted to communicate with

the boats using a hand-held Aldis lamp. The tiny signaling device was

useless. It could not penetrate the smoke surrounding the bridge.

Larkins, who had not heard McGonagle's "hold fire" order,

suddenly released a wild and ineffective burst of machine-gun fire and

was quickly silenced by the captain. Immediately, the gun mount astern

of the bridge opened fire, blanketing the center boat. McGonagle called

for that gunner, too, to cease fire, but he could not be heard above the

roar of the gun and the loud crackle of flaming napalm. Although less

than twenty feet apart, McGonagle was separated from the gun by a wall

of flame. Lucas ran through the pilothouse and around a catwalk, trying

to reach the gun. Finally, when he could see over a skylight and into

the gun tub, he found no gunner. The gun mount was burning with napalm,

causing the ammunition to cook off by itself. The mount was empty.

Heavy machine-gun fire from the boats saturated the bridge. A

single hardened steel, armor-piercing bullet penetrated the chart house,

skimmed under the Loran receiver, destroyed an office paper punch

machine, and passed through an open door into the pilothouse with just

enough remaining force to bury half its length in the back of the neck

of brave young helmsman Quartermaster Francis Brown, who died instantly.

Ensign Lucas, seeing Brown fall and not knowing what had hit

him or from which direction it had come, stepped up to take his place at

the helm.

A torpedo was spotted. It passed astern, missing the ship by

barely seventy-five feet.

--END OF CHAPTER SIX--

FOOTNOTES:

1. This story first came to me from an enlisted crew member of the

submarine, who blurted it out impulsively in the cafeteria at Portsmouth

Naval Hospital a few weeks after the attack. The report seemed to

explain the marks I had seen on the chart in the coordination center, as

well as reports of periscope sightings that circulated in the ship on

the day of the attack. Since the attack, three persons in positions to

know have confirmed the story that a submarine operated near Liberty,

although no credible person has confirmed the report that photographs

were taken.

2. The jet aircraft that initiated the attack were Dassault Mirage Ill

single-seat long-range 1,460mph (Mach 2.2) fighter bombers similar to

those seen during the morning. Mirages carry 30mm cannon in the fuselage

and thirty-six rockets under the wings. The follow-up jet attack was

conducted by Dassault MD-452 Mystyre IV-A single-seat 695mph (Mach 0.9

1) jet interceptors. Mystyres typically carry two 30mm cannon,

fifty-five rockets, and napalm canisters. None of the attacking aircraft

was identified as to either type or nationality until much later, when

comparison was made with standard warplane photographs.

3. See Appendix B. Liberty appealed for help commencing 1158Z (1358

ship's time) and continuing for more than two hours, remaining silent

only when the ship was without electrical power. At 140*OZ, two hours

after the commencement of the attack, Liberty Radioman Joe Ward

transmitted: "Flash, flash, flash. I pass in the blind. We are under

attack by aircraft and high-speed surface craft. I say again, Flash,

flash, flash. We are under attack by aircraft and high-speed surface

craft." At 1405Z (1605 ship's time) Ward came on the air again to say,

"Request immediate assistance. Torpedo hit starboard side." These times

are important, as Liberty was under fire untit 1315Z, was confronted by

hostile forces until 1432Z, and was in urgent need of assistance the

entire time.

4. Saratogau misidentified the ship as USNS Liberty. USNS ships are

civilian- manned and operate under contract with the Navy, USS ships are

manned by American sailors and are commissioned by the United States.

5. Rear Admiral Lawrence Raymond Geis: naval aviator; born 1916; U.S.

Naval Academy, class of 1939 promoted to rear admiral July 1, 1965 was

commanding officer, USS Forrestal (CVA 59) 1962-63 would be assigned to

duty in September 1968 as Chief of Naval Information. The Office of

Naval Information has long played a leading role in the cover-up of the

USS Liberty story.

6. Saratoga's repeated demand for authentication, coupled with errors

and possible delay in forwarding Liberty's messages, contributed to

confusion at CINCUSNAVEUR headquarters. Liberty's first appeal for help,

received by Saratoga at 1209Z, was forwarded at Immediate precedence to

CINCUSNAVEUR headquarters. Immediate precedence, however, is entirely

inadequate as a speed-of-handling indicator for enemy contact reports;

more than 30 percent of the messages glutting the communication system

are Immediate precedence or higher. Liberty's second appeal was

appropriately forwarded at the much faster Flash precedence, overtaking

the initial report to arrive at CINCUSNAVEUR at 1247Z with the damning

notation that it was not authenticated. Thus the first Teletype report

of Liberty's attack arrived in London with the misleading caveat that

the transmission could be a hoax. The earlier report, arriving eight

minutes later, failed to mention that Liberty's initial transmission was

authenticated. Not until 1438Z, as the attack ended and Israel

apologized, did CINCUSNAVEUR learn from Saratoga (USS Saratoga message

081358Z June 1967) that the initial report was indeed authenticated.

7. Captain Donald Davenport Engen: naval aviator; born 1924; first

commissioned 1943; University of California at Los Angeles, class of

1948; holds nation's second-highest award for bravery, the Navy Cross.

Would be promoted to rear admiral in 1970 and to vice admiral in 1977.

8. COMSIXTHFLT message 081305Z June 1967 (Appendix C, page 236)

promises: SENDING AIRCRAFT T0 COVER YOU. This message, released on the

flagship about fifty-five minutes after Liberty's first call for help,

was not the first such message. Liberty crewmen, including the writer,

recall reports of help on the way at about 122OZ while the ship was

still under air attack.

9. Months later Hart was visited by an agent of the Naval Investigative

Service--armed with notebook and tape recorder--who sought to "debrief'

him on the events of June 8; that is, to record for the record

everything that Hart could recall of the attack and the communications

surrounding it. Hart refused to discuss the attack and the man went

away. Hart never heard from him again.

|

Where to order Jim's book.

Where to order Jim's book. Hear this chapter read by Dick Estelle, as heard on National Public Radio.

Hear this chapter read by Dick Estelle, as heard on National Public Radio.